Chapter 3 Ethical data practice

Learning objectives

- Define reproducibility in the context of scientific research

- List, discuss, and employ good coding practice

- Define data sovereignty and explain this in relation to a researcher’s obligation when collecting, displaying, and analysing data

- Define and discuss Māori Data Sovereignty principles

- Discuss the responsibility of researchers in presenting and communicating research

- Critically evaluate science publications by assessing the appropriateness and accuracy of conclusions drawn

When we handle data we should always be accurate, honest, respectful and act responsibly. That seems obvious, right? But what does this mean in practice?

There are many ongoing discussions in the scientific community around ethical data practice and what it entails. It is a hugely important subject, and in many ways has a long way to go. We only touch briefly on some aspects of ethical data practice in this section, presenting the suggestions and thoughts of trailblazing communities and organisations in those areas.

Accuracy and Honesty: Being accurate and honest in your analyses and conclusions.

Respectful Handling of Data: Recognize that data may represents people or beliefs or behaviour and be respectful of this.

Awareness of Consequences: Considering the ethical implications and societal impact of your research.

TASK Read Ethical Guidelines for Statistical Practice and outline which principle(s) you feel directly relate to your current career pathway.

3.1 Accuracy and Honesty

Honesty is an expectation: we expect honesty from you and you expect the same from your teaching team. Honesty is an expectation in any scientific discipline as is accuracy. These are morals, ethical principles we should abide by. But this course isn’t here to discuss philosophy or character development. This course, in particular this section of the course, is to expose you to the tools and principles that will aid you in your own pursuit of ethical data practice.

This course doesn’t , teaching you the tools so that your analysis is reproducible goes someway towards accuracy. This because, reproducibility promotes transparency, facilitates error detection and correction, and contributes to the overall reliability and accuracy of your research findings.

3.1.1 Reproducibility

“Reproducibility, also known as replicability and repeatability, is a major principle underpinning the scientific method. For the findings of a study to be reproducible means that results obtained by an experiment or an observational study or in a statistical analysis of a data set should be achieved again with a high degree of reliability when the study is replicated. … With a narrower scope, reproducibility has been introduced in computational sciences: Any results should be documented by making all data and code available in such a way that the computations can be executed again with identical results.”

Reproducibility is a stepping stone towards ensuring accuracy. This is because, reproducibility promotes transparency, facilitates error detection and correction, and contributes to the overall reliability and accuracy of your research findings. Establishing good practice when dealing with data and code right from the beginning is essential. Good practice 1) ensures that data is collected, processed, and stored accurately and consistently, which helps maintain the quality and integrity of the data throughout its lifecycle; and 2) creates a robust code base, which can be easily understood and adapted as the project progresses, which leads to faster development.

3.1.2 Good coding practice

Always start with a clean workspace Why? So your ex (code) can’t come and mess up your life!

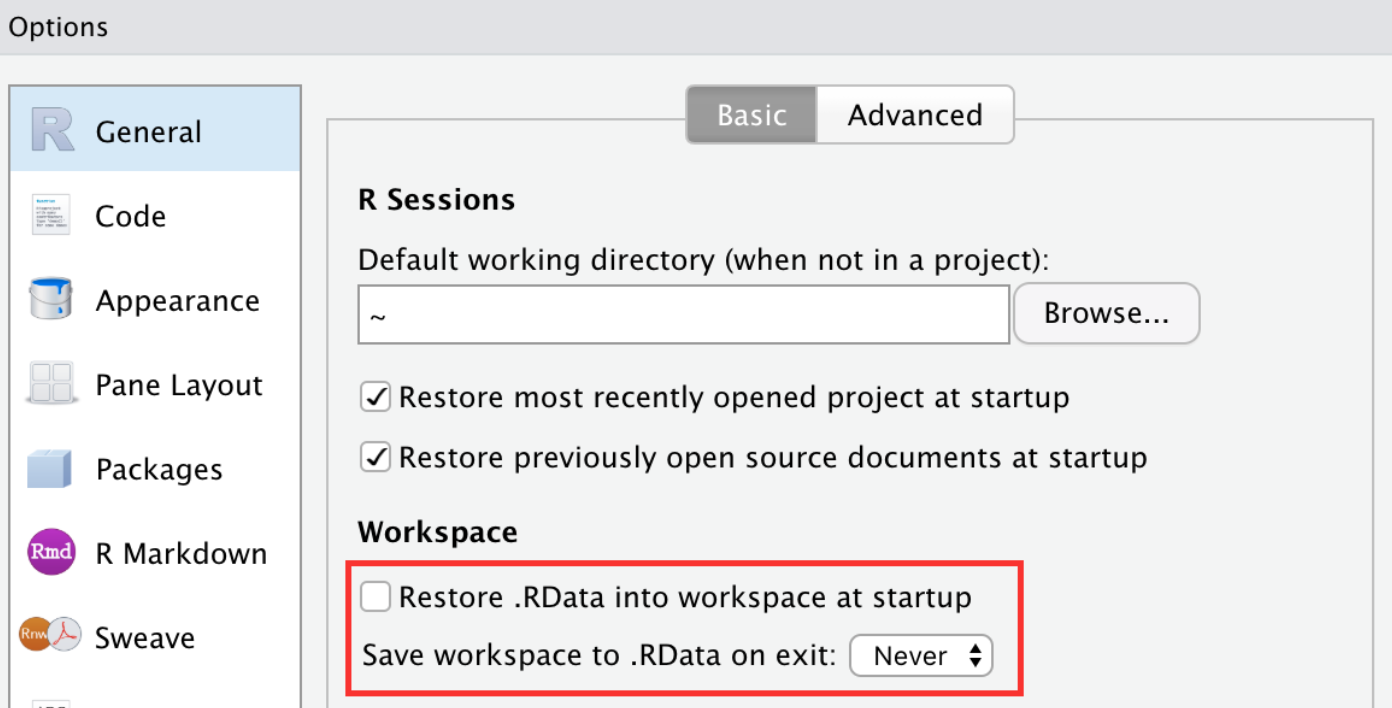

To ensure this go to Tools > Global Options and uncheck the highlighted options.

Why? Because, this is not reproducible, does NOT create a fresh R process, makes your script vulnerable, and it will come back to bite you.

TASK Below are two quotes from Jenny Bryan, an R wizard which reference two snippets of R code. Find out what each snippet does and why Jenny is so against them.

If the first line of your R script is

setwd("C:\Users\jenny\path\that\only\I\have")

I will come into your office and SET YOUR COMPUTER ON FIRE 🔥.

If the first line of your R script is

rm(list = ls())

I will come into your office and SET YOUR COMPUTER ON FIRE 🔥.

A project-oriented workflow in R refers to a structured approach to organizing and managing your code, data, and analyses. This helps improve reproducibility and the overall efficiency of your work. Within this it is essential essential to write code that is easy to understand, maintain, and share. To do so, coding best practice is to follow the 5 Cs by being

- Clear

- Code Clarity: Write code that is easy to read and understand. Use meaningful variable and function names that convey the purpose of the code. Avoid overly complex or ambiguous expressions.

- Comments: Include comments to explain the purpose of your code, especially for complex or non-intuitive sections. Comments should add value without stating the obvious.

- Concise:

- Avoid Redundancy: Write code in a way that avoids unnecessary repetition. Reuse functions and use loops or vectorized operations when appropriate to reduce the length of your code.

- Simplify Expressions: Simplify complex expressions and equations to improve readability. Break down complex tasks into smaller, manageable steps.

- Consistent:

- Coding Style: Adhere to a consistent coding style throughout your project. Consistency in indentation, spacing, and naming conventions makes the code visually coherent.

- Function Naming: Keep naming conventions consistent. If you use camelCase for variable names, continue to use it consistently across your codebase.

- Correct:

- Error Handling: Implement proper error handling to ensure that your code gracefully handles unexpected situations. Check for potential issues, and provide informative error messages.

- Testing: Test your code to ensure it produces the correct output. Use tools like unit tests (e.g., with

testthat) to verify that your functions work as intended.

- Conformant:

- Follow Best Practices: Adhere to best practices and coding standards in the R community. For example, follow the tidyverse style guide or the Google R Style Guide.

- Package Guidelines: If you’re creating an R package, conform to package development guidelines. Use the

usethispackage to help set up your package structure in a conformant way.

There are many other good practice tips when it comes to coding these include ensuring your code is modular, implementing unit testing, automating workflows and implementing version control. These topics, however are beyond the scope of this course (take BIOSCI738 if you’d like to learn more about them).

3.2 Respectful Handling of Data

3.2.1 Data sovereignty

The term data sovereignty has a hugely broad range of connotations. We do not aim to cover them all in this course. Typically, data sovereignty is focused on the understanding and adhering to the legal and ethical considerations associated with data collection, storage, and analysis in different jurisdictions. Researchers are expected follow and abide by the best ethical and legal practice whilst respecting individuals’ privacy and rights.

“For Indigenous peoples, historical encounters with statistics have been fraught, and none more so than when involving official data produced as part of colonial attempts at statecraft.”

Indigenous data sovereignty refers to the right or interest indigenous peoples and nations have to govern the collection, ownership, and application of their own data. As we are in Aotearoa this is most pertinent in the terms of māori data sovereignty.

3.2.2 Māori Data Sovereignty principles

“Māori Data Sovereignty has emerged as a critical policy issue as Aotearoa New Zealand develops world-leading linked administrative data resources.”

Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi obliges the Government to actively protect taonga, consult with Māori in respect of taonga, give effect to the principle of partnership and recognize Māori rangatiratanga over taonga.

TASK There are many ongoing discussions that surround the Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi, focused mainly on whether the statements of principles it outlines have been upheld. What do you think? Can you find a recent event/news article that relates to your studies, which either clearly upholds, or not, what you deem to be the correct ethical practice here?

Māori Data Sovereignty principles inform the recognition of Māori rights and interests in data, and promote the ethical use of data to enhance Māori wellbeing.

The Te Mana o te Raraunga Model was developed to align Māori concepts with data rights and interests, and guide agencies in the appropriate use of Māori data. Below are the guiding principles outlined by Te Mana o te Raraunga Model in th e Principles of Māori Data Sovereignty.

Rangatiratanga (authority)

- Māori have an inherent right to exercise control over Māori data and Māori data ecosystems. This right includes, but is not limited to, the creation, collection, access, analysis, interpretation, management, security, dissemination, use and reuse of Māori data.

- Decisions about the physical and virtual storage of Māori data shall enhance control for current and future generations. Whenever possible, Māori data shall be stored in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Māori have the right to data that is relevant and empowers sustainable self-determination and effective self-governance

Whakapapa (relationships)

- All data has a whakapapa (genealogy). Accurate metadata should, at minimum, provide information about the provenance of the data, the purpose(s) for its collection, the context of its collection, and the parties involved.

- The ability to disaggregate Māori data increases its relevance for Māori communities and iwi. Māori data shall be collected and coded using categories that prioritise Māori needs and aspirations.

- Current decision-making over data can have long-term consequences, good and bad, for future generations of Māori. A key goal of Māori data governance should be to protect against future harm.

Whanaungatanga (obligations)

- Individuals’ rights (including privacy rights), risks and benefits in relation to data need to be balanced with those of the groups of which they are a part. In some contexts, collective Māori rights will prevail over those of individuals.

- Individuals and organisations responsible for the creation, collection, analysis, management, access, security or dissemination of Māori data are accountable to the communities, groups and individuals from whom the data derive

Kotahitanga (collective benefit)

- Data ecosystems shall be designed and function in ways that enable Māori to derive individual and collective benefit.

- Build capacity. Māori Data Sovereignty requires the development of a Māori workforce to enable the creation, collection, management, security, governance and application of data.

- Connections between Māori and other Indigenous peoples shall be supported to enable the sharing of strategies, resources and ideas in relation to data, and the attainment of common goals.

Manaakitanga (reciprocity)

- The collection, use and interpretation of data shall uphold the dignity of Māori communities, groups and individuals. Data analysis that stigmatises or blames Māori can result in collective and individual harm and should be actively avoided.

- Free, prior and informed consent shall underpin the collection and use of all data from or about Māori. Less defined types of consent shall be balanced by stronger governance arrangements.

Kaitiakitanga (guardianship)

- Māori data shall be stored and transferred in such a way that it enables and reinforces the capacity of Māori to exercise kaitiakitanga over Māori data.

- Ethics. Tikanga, kawa (protocols) and mātauranga (knowledge) shall underpin the protection, access and use of Māori data.

- Māori shall decide which Māori data shall be controlled (tapu) or open (noa) access.

3.3 Awareness of Consequences

Considering the implications and societal impact of your research includes ensuring that any conclusions you draw are appropriately and accurately balanced. Consider the previous chapter Data Visualization, the guiding principles of making informed visualizations included not misleading readers and prioritizing conveying a clear message. These speak to being mindful of how your figures may be perceived and presenting your data ethically and responsibly.

Your responsibilities go beyond just making figures, they extend to the methods and inferences you draw. Learning how to communicate science is a key and invaluable skill. Siouxsie Wiles, is an award winning science communicator and is perhaps best known for stepping up during the pandemic giving us information about the virus and advice on how to beat it.

“I assumed it would be through my research by helping develop a new antibiotic. But through the pandemic, I’ve learned that I can have a huge impact globally by doing good science communication.”

Below is a case study in science (mis)communication.

3.3.1 Case study

Asthma carbon footprint ‘as big as eating meat’ is the headline of this news story published on the BBC website. The article is based research outlined in this published paper which in turn cites this paper for an estimate of the carbon footprint reduced by an individual not eating meat.

It is not unreasonable to assume that many people would interpret this to mean that the total global carbon footprint due to eating meat is equal to the total carbon footprint due to the use of asthma inhalers. However, this is not what they mean. They mean that an individual deciding not to eat meat reduces their carbon footprint as much as an asthmatic individual deciding not to use an inhaler.

There are far more meat consumers compared to inhaler users and so the overall carbon footprint associated with meat consumption is much greater. However, the claim that not eating meat reduces someone’s carbon footprint about the same amount as not using inhalers is questionable. Yet, both the BBC article and the paper make this claim.

“And at the individual level, each metered-dose inhaler replaced by a dry powder inhaler could save the equivalent of between 150kg and 400kg (63 stone) of carbon dioxide a year - similar to the carbon footprint reduction of cutting meat from your diet.”

“Changing one MDI device to a DPI could save 150–400 kg CO2 annually; roughly equivalent to installing wall insulation at home, recycling or cutting out meat.”

Now, the the carbon footprint of eating meat is estimated as 300–1600 kg CO2 annually by this paper (see Table 1). And so the two claims don’t really match up. Moreover, what is being suggested by the article? That should asthmatics should think about ceasing their medication in the same way many people are trying to reduce meat consumption?!?

In this section we’ve discussed how ethical data practice involves accuracy, respect, and clear communication. There is one other component that should be considered here and that is consequence. The two options in this case study are not balanced because they have very different consequences:

- Not eating meat is (possibly) good for you and is also good for the planet, but

- Not taking your inhaler is (probably) much worse for your health.

TASK Watch this lecture Algorithmic fairness: Examples from predictive models for criminal justice and summarise the key points made. Can you think of a recent story that highlights the issues raised?

Other resources: optional but recommended